Listen to the audio version >>

Unilateral US dominance is increasingly challenged in the era of overlapping crises that is now often being referred to as “the polycrisis.” This has led many countries to advocate for what they call “polycentrism,” a world order in which no single country is dominant. But simply having a larger number of elites plundering their own and other countries is unlikely to provide a solution to the polycrisis. That requires that countries pursue not only interests of their own elites, but the common global interest that has been so rubbished in the unipolar era.

What will follow the end of US global hegemony? The buzzword of the day is “polycentrism.”

While no other country – not even Russia or China – believes it can replace the US as global hegemon, many proclaim or at least aspire to a new “polycentric” world order. This is often portrayed as a replacement of US domination by a renascent era of national sovereignty. The reality of polycentrism, however, is rather different.

It is true that the decline of US hegemony has given countries in the Global South more room to maneuver, both in implementing their own development policies and in achieving a degree of leverage by playing the great powers off against each other. According to the “Second Cold War,” a perceptive study of great power rivalry in the era of polycrisis, a globalized economy has devolved not into national economies, but into great power rivalry to hegemonize transnational networks.

This rivalry allows many national governments across Asia, Africa, and Latin America to “resist pressure to align exclusively with Beijing or Washington.” In contrast to the original Cold War, “the allegiance of third countries and their populations is partial and contingent because network connections can be reconfigured with relative ease.” They give as an example how, upon taking office, former Tanzanian President Magufuli indefinitely suspended plans to construct Bagamoyo Port, which was under contract with a Chinese firm and would have been Africa’s largest port.[1] Countries can even parcel out their alignment with greater powers. “The US may integrate a country into production networks anchored by its multinational lead firms, while China may simultaneously integrate the same country into its digital and/or infrastructure networks.”[2]

But changing or dividing alignments is not the same as escaping the pressures for alignment and achieving freedom of action. An article in Financial Times (FT) describes how G42, a leading Persian Gulf artificial intelligence company, has been pressured to cut ties with Chinese hardware suppliers in favor of US companies, in what FT characterizes as “a sign of the growing geopolitical struggle over the new technology.”

G42 of the United Arab Emirates is making the move to ensure its access to US-made chips by allaying concerns among its American partners, which include Microsoft and OpenAI, chief executive Peng Xiao said.

“For better or worse, as a commercial company, we are in a position where we have to make a choice,” Xiao told the FT. “We cannot work with both sides. We can’t.”

Xiao said G42 was phasing out hardware from Huawei, which had provided servers and data center networking gear. He added that G42 had decided to pull back from its China relationships to appease its US corporate partners and to ensure it complied with Washington’s rules on exports of advanced chips.

The UAE sees itself as a node within a new multipolar world, where China, India and Russia have emerged as counterpoints to the west’s historic economic dominance. But the global scramble for AI chips, particularly those made by US chipmaker Nvidia, has limited Abu Dhabi’s room to pivot away from Washington’s orbit.

The UAE chose Huawei to install the first national 5G infrastructure in 2019, despite US objections, citing an unavailability of similar technology from western partners promoted by Washington. Since then, however, state companies have signed further deals with Sweden’s Ericsson as the UAE pursues a policy of diversifying its telecommunications partners.[3]

The US’ burgeoning use of sanctions, notably against countries that refuse to cut ties with Russia over the Ukraine war, further limits developing countries’ freedom of action. According to Tim Sahay, co-director of the Net Zero Industrial Policy Lab at Johns Hopkins University,

After the US threatened any client for Russian weapons with economic warfare, Indonesia cancelled its planned purchase of Russia’s Sukhoi-35 fighter jets, despite Russian offers of a dollar bypass palm-oil-for-fighter-jets scheme. Instead, Indonesia undertook a major escalation in defense spending to buy thirty-six US F-15s and forty-two Rafales from France, along with two of France’s Scorpene submarines. When Russia shipped two S-400 air defense missile systems to India in 2021, it prompted a furious backlash from the US and threats to sanction India for the deal.[4]

Continuing dependence on transnational networks poses a problem not only for established national rulers but also for national revolutions and uprisings. Although they may be able to dethrone an autocratic ruler, their ability to change the conditions of national dependence may be limited to choosing among networks dominated by major powers.[5]

While “polycentrism” has been widely advocated as the alternative to unilateral US hegemony, advocacy for a multipolar world and opposition to great power domination are not necessarily steps toward ameliorating the problems of ordinary people, let alone toward international cooperation to address global problems. As a review of the 2023 “Year of Crises” put it, “One should have no illusions about the radicalism of a new non-aligned movement.” The ruling elites of these countries are rarely concerned with “carving out more policy space and autonomy for their publics.”[6] It is not clear how much ordinary people will benefit from “the anti-imperialism of the ruling class.”[7]

Far from being the basis for reestablishing national sovereignty as a fundamental principle of the world order, today’s “polycentrism” can be a polite term for a cruel and violent struggle among the great and near-great powers with few restraints on their willingness to harm the less great.

Indeed, according to Sahay, countries like China, India, Indonesia, Brazil, South Africa, Mexico, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates have “aspirations for regional dominance.” The developing country resistance to US pressure to sanction Russia after its Ukraine invasion “is no bleeding-heart protest for global justice, but a hard-nosed security play.” [8]

It is not yet clear whether even this limited form of polycentrism will be an ongoing feature of the polycrisis era, or whether it is evolving toward a new bloc system. According to “The Second Cold War,”

The stronger the imperative to choose between membership in US- or Sino-centric networks, the more likely the formation of territorial blocs reminiscent of the first Cold War becomes. If forced to align fully with the US or China, the world may indeed splinter into two rival blocs, each with its own parallel networks that barely, if at all, intersect. For example, the future may witness the emergence of two, largely disconnected Internets, the decoupling of certain Global Production Networks global payment systems, and the continued expansion of Sino-centric financial networks.[9]

The polycentric world order that characterizes the era of polycrisis does little to create genuine freedom for the people who have escaped US unilateral hegemony only to become the pawns of great power rivalry. Nor does it do much to address such fundamental problems facing the world as climate change, environmental degradation, poverty, inequality, arms races, war, and nuclear holocaust.

In 1955, at the height of the Cold War, 29 countries held a conference at Bandung, Indonesia and established the Non-Aligned Movement of countries that were neither colonies not formally aligned with either Eastern or Western power blocs. It eventually included 120 members.[10] It advocated for decolonization, anti-racism, and nuclear disarmament in the UN General Assembly and elsewhere. It launched a global campaign for a North-South dialogue to establish a New International Economic Order that would regulate global markets in the interest of the development process — only to have that dialogue brought to a halt by a newly elected US president Ronald Reagan. The Non-Aligned Movement passed from relevance with the end of the Cold War and the rise of unipolar US dominance.

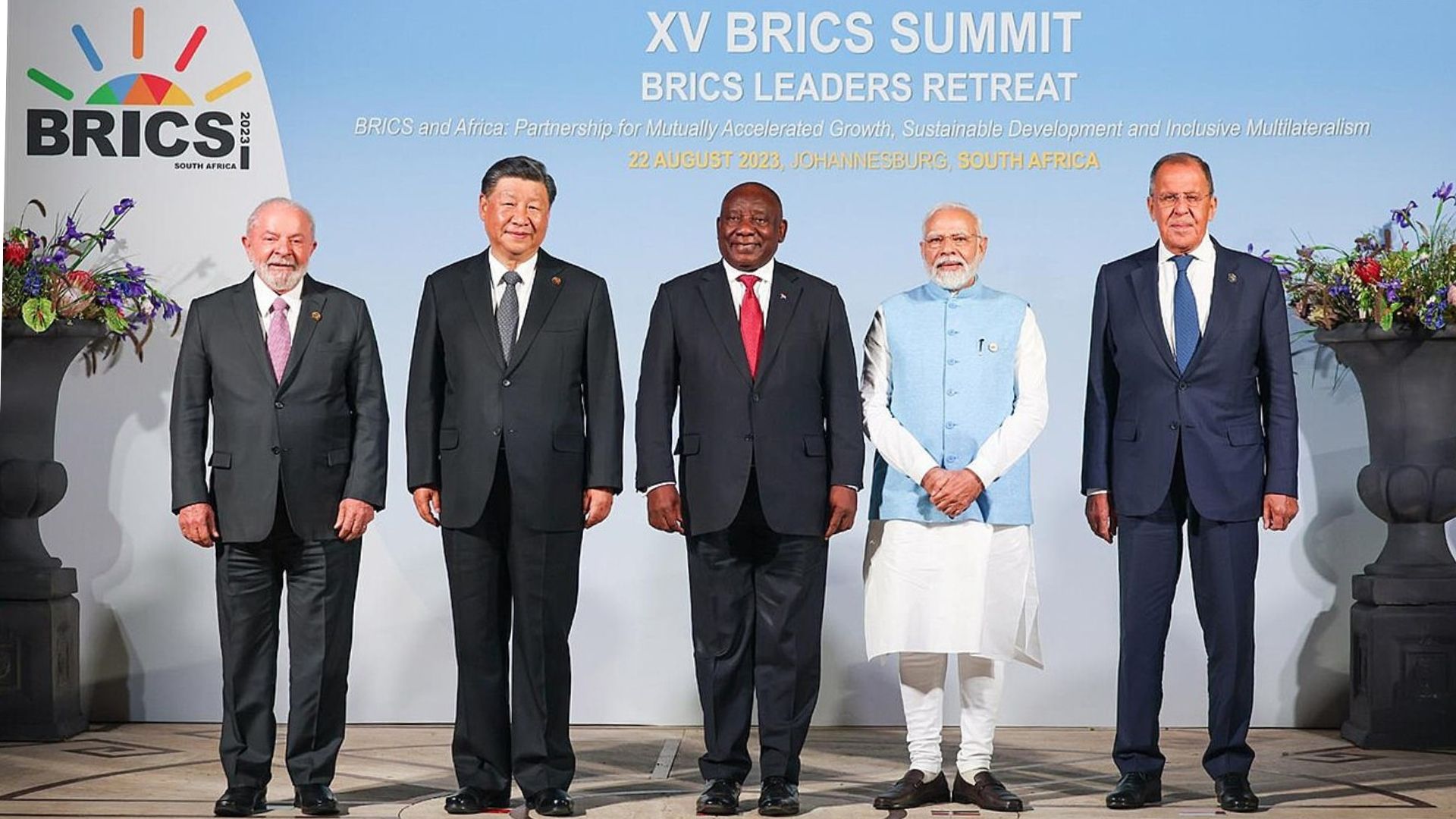

At a 2009 summit, major non-Western countries Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa formed a grouping known as BRICS; they have recently been joined by Saudi Arabia, Iran, and others to form “BRICS Plus.” Its purpose was to create a counterweight to Western power. But the BRICs countries are far from united, with major conflicts for example between India and China. The idea of a BRICS currency to provide an alternative to the global domination by the dollar has been widely discussed for several years but is far from realization. In 2015 BRICS created the BRICS Bank, now known as the New Development Bank, but it has so far played only a minor role in reducing dependence on Western finance.[11] The bank has abided by US sanctions against cooperation with Russia.

BRICS representatives at the 2023 summit: (From left) President of Brazil Lula da Silva, President of China Xi Jinping, President of South Africa Cyril Ramaphosa, Prime Minister of India Narendra Modi and Foreign Minister of Russia Sergey Lavrov, in a family photograph during the BRICS Leaders Retreat Meeting, at Johannesburg, in South Africa on August 22, 2023. Pho Credit: GODL-India, Wikipedia Commons

According to Sahay, whereas the original Non-Aligned Movement was anchored by “moral imperatives” like decolonization, anti-racism, and nuclear disarmament, today’s increasing self-assertion by non-Western countries “lacks a positive social and ethical program.” Instead, “it stems from the cold commercial and security logic of development.”

There are some seeds of potential alternatives to the polycrisis within the current pursuit of polycentrism. Brazil’s president Luiz Inacio Lula de Silva (“Lula”) has promised to focus on “the reduction of inequalities,” including social inclusion and hunger reduction; energy transition and sustainable development; and global governance reform.[12] Richard Falk, international law professor and former UN Special Rapporteur on human rights in the occupied Palestinian territories, recently noted that during the Gaza crisis there have been some “very robust popular movements” and actions by the International Court of Justice and the International Criminal Court that have come from “the initiatives taken by countries in the Global South.” But “this has to become a much stronger movement challenging hegemonic world order.” The Global South needs to emerge as “a much more forceful presence in the organization of the world and of the reform of the UN.”[13]

The illustrator Marc Simont once told me a story told him by his father, a well-known portraitist. He was painting Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau, who was representing France at the peace conference that was negotiating the Treaty of Versailles at the close of World War I. Clemenceau said to the artist, “You know what they’re doing here, don’t you? They’re choosing up sides for World War II.” Notwithstanding all its complexities, much of what is going on in the polycrisis can be understood as choosing up sides for World War III.

[1] Seth Schindler et al., “The Second Cold War,” Taylor & Francis online, Volume 29, 2024 – Issue 4, September 7, 2023. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/14650045.2023.2253432?src=

[2] Ibid. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/14650045.2023.2253432?src=

[3] Michael Peel and Simeon Kerr, “UAE’s top AI group vows to phase out Chinese hardware to appease US,” Financial Times, December 8, 2023. https://www.ft.com/content/6710c259-0746-4e09-804f-8a48ecf50ba3

[4] Tim Sahay, “A New Non-Alignment,” Phenomenal World, November 9, 2022. https://www.phenomenalworld.org/analysis/non-alignment-brics/

[5] For failures of national uprisings and revolutions to change the dependent status of nations, see Vincent Bevans, If We Burn, Hachette Book Group, 2025. https://www.hachettebookgroup.com/titles/vincent-bevins/if-we-burn/9781541788985/?lens=publicaffairs

[6] Tim Sahay, “A Year in Crises,” Phenomenal World, December 21, 2023. https://www.phenomenalworld.org/series/the-polycrisis

[7] William Shoki, referring to BRICs. For more on the “new non-alignment,” see Tim Sahay, “A New Non-Alignment,” Ibid. https://www.phenomenalworld.org/analysis/non-alignment-brics/

[8] Sahay, Ibid. https://www.phenomenalworld.org/analysis/non-alignment-brics/

[9] Aaron Donaghy, “Second Cold War,” Cambridge University Press, April 29, 2021. https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/abs/second-cold-war/introduction/0BE79FA9CC2C557CDF3383673F7B032F

[10] Tracy Lyon, seminar re: Tim Sahay, “The Non-Aligned Movement Disarmament Database,” Middlebury Institute of International Studies at Monterey, May 24, 2017. https://nonproliferation.org/the-non-aligned-movement-disarmament-database/

[11] For further discussion of BRICS, see Patrick Bond and Ana Garcia, BRICS: An Anti-Capitalist Critique, London: Pluto, 2015. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26414063

[12] Jordana Timerman, “Lula is styling himself as the new leader of the global south,” Guardian, April 29, 2024. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2024/apr/09/brazil-g20-lula-west-global-south

[13] Serdar Dincel, “Global South has key role to play in ending Israel’s war on Gaza, reforming world order: UN rapporteurs,” AA, August 8, 2024. https://www.aa.com.tr/en/world/global-south-has-key-role-to-play-in-ending-israel-s-war-on-gaza-reforming-world-order-un-rapporteurs/3298891