As key states start reducing their use of coal, oil, and gas, what will happen to the workers who produce, transport, and burn those fossil fuels? The previous Commentary, “Protecting Workers and Communities – From Below: Part 1: On the Ground” described local programs to protect workers and communities from side effects of power plant closings and other climate protection measures. This Commentary portrays state-level programs to guard workers and communities against loss of livelihoods and income from climate protection policies.

While the transition to climate-safe energy will create far more jobs than it will eliminate, that is cold comfort for those whose jobs may be threatened – after all, every job is important if it is your job. So many of those who are advocating for state policies for climate protection are also advocating protections for workers and communities that may be adversely affected by climate measures. And many of the states that are transitioning away from climate-destroying fossil fuels to climate-safe renewable energy are developing policies and programs to protect workers and communities from damaging side effects of that transition. While such provisions are still far from adequate, they provide initial experiments that can lay the groundwork for expanded protections at both state and national levels.

Washington: Pioneer

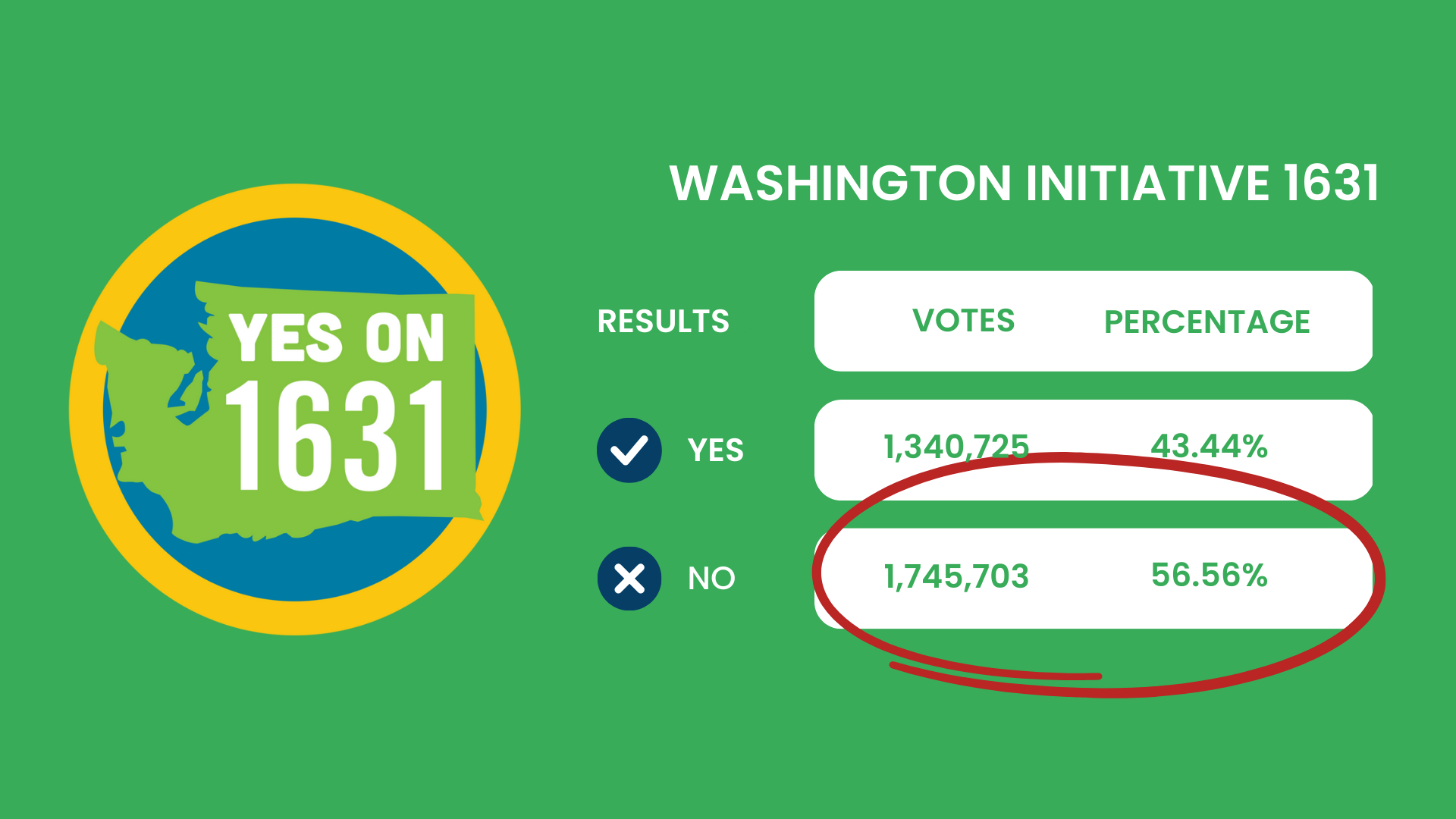

Source: Ballotpedia.org

Those who pioneer a new policy don’t always win, but sometimes they blaze a trail that opens the way for others to follow. That is what happened with the Washington State Initiative 1631, which was narrowly defeated at the polls in 2018 but which has been the inspiration for a string of subsequent state legislative efforts that have taken it as a model.

In 2008 the state of Washington passed a law that required that greenhouse gas emissions be reduced to 1990 levels by 2020, 25% below 1990 levels by 2035, and 80% below 1990 levels by 2050. Numerous proposed laws and ballot initiatives to implement these objectives failed. In 2014 seven leaders representing communities of color, environmentalists, tribes, and labor formed the Alliance for Jobs and Clean Energy. According to Jeff Johnson, then president of the Washington State Labor Council, AFL-CIO, and one of the founders of the Alliance, the coalition spent three years “building a climate justice movement based on principles of equity and giving assistance and voice to those most disproportionately impacted by climate disaster.”[1]

According to Aiko Schaefer, leader at the time of Front and Centered, an umbrella organization of low-income and community-of-color groups,

Frontline and communities of color came together with workers, environmentalists, public health leaders, and so many others to put our heads together to create what works best for our state.” It is “the embodiment of an inclusive democracy.”[2]

Climate journalist David Roberts described this as a “coalition-first, policy-second approach.”

A 2017 report on “A Green New Deal for Washington State” by Robert Pollin laid out a program for realizing the climate, justice, and labor goals of the Green New Deal.[3] This became the basis for the Alliance for Jobs and Clean Energy’s Initiative 1631.

Initiative 1631 was based on the principle that polluters should pay for the social costs of halting their pollution. The ballot title summarizing the Initiative said it would “charge pollution fees on sources of greenhouse gas pollutants” and use the revenue to “reduce pollution, promote clean energy, and address climate impacts” under oversight of a public board. It charged a fee for each ton of carbon emitted, starting at $15 a ton and increasing $2 every year until the state’s greenhouse gas emission target for 2035 was met and its target for 2050 was on track to be met; the fee was expected to generate more than $2 billion over five years.

The revenue from the pollution fees would be used for climate-protecting investments related to transportation, energy efficiency, carbon sequestration in farms and forests, and clean energy, as well as climate adaptation forestry and water conservation projects. A public accountability board with voting representatives from unions, local communities, environmental justice groups, and indigenous tribes would oversee the distribution of funds. A minimum of 35% of all investments would be allocated to benefit pollution-burdened environmental justice communities; 15% would assist lower-income populations; and 10% of investments would require formal support from a tribal government, with the stipulation that projects on tribal lands receive Free Prior and Informed Consent from the tribe.

Many of its provisions were designed to ensure just outcomes for the constituencies in the Alliance, including:

- Heating and electric assistance to low-income families.

- 35% of carbon revenue into disproportionately impacted communities.

- High labor standards: prevailing wages, apprenticeship utilization, community workforce agreements with local hire, clean record of employers on labor rights and health and safety.

- An Exemption for Energy Intensive Trade which exempted trade-exposed industries from the pollution fee but not from requirements to lessen carbon emissions to prevent the “leakage” of pollution and jobs out of state.

- Fifteen-member oversight committee whose majority represented communities of color, tribes, environment, public health and labor. Those most impacted by climate disaster were put in the role of making the decisions about where clean energy investments would be made.

An unprecedented aspect of Initiative 1631was its earmarking of funds from the pollution fee to provide support for fossil fuel workers whose livelihoods might be harmed by the transition away from fossil fuel energy. It provided that at least fifty million dollars must be “set aside, replenished annually, and maintained” for a worker-support program for bargaining unit and nonsupervisory fossil fuel workers who are “affected by the transition away from fossil fuels to a clean energy economy.” Worker support could include but was not limited to:

- full wage replacement, health benefits, and pension contributions for every worker within five years of retirement;

- full wage replacement, health benefits, and pension contributions for every worker with at least one year of service for each year of service up to five years of service;

- wage insurance for up to five years for workers reemployed who have more than five years of service;

- up to two years of retraining costs including tuition and related costs, based on in-state community and technical college costs;

- peer counseling services during transition;

- employment placement services, prioritizing employment in the clean energy sector;

- relocation expenses;

- and any other services deemed necessary by the environmental and economic justice panel.[4]

The Alliance for Jobs and Clean Energy built a campaign organization with Climate Justice Stewards in every part of the state. Initial polling on Initiative 1631 was consistently positive.

According to Jeff Johnson, unions representing more than 60% of the 450,000 members of the Washington State Labor Council, AFL-CIO supported Initiative 1631. Some unions, mostly in the building trades, opposed the initiative on the grounds that it would cost their members more money and/or crowd out dollars for investing in transportation projects.

Shortly before the election the Yes campaign had raised a little over $5 million; the No campaign had raised $20 million, overwhelmingly from oil and gas interests. Then began an onslaught of ads attacking 1631. Exxon alone spent over $30 million for anti-Initiative television ads in the last days of the campaign. Ultimately initiative 1631 was defeated 56-44%.

Despite this defeat, Initiative 1631 became the inspiration and model for subsequent worker and community coalition efforts, transition programs, and protection measures in Colorado, Illinois, California, and elsewhere.

Colorado’s Office of Just Transition

In 2018, a Democratic bill in the Colorado legislature called for 100% renewable energy by 2035. The bill was doomed in the Republican legislature, but it was a wakeup call for Colorado unions. According to Dennis Dougherty, executive director of the Colorado AFL-CIO, which includes 165 unions representing more than 130,000 workers,

It forced the conversation on our end as to what do we need to do to get behind these bills in the future, instead of just blocking them or delaying. It was really the first time we asked ourselves, well what’s our game plan?[5]

That year a coalition of community, faith, youth, and environmental groups launched the People’s Climate Movement Colorado, affiliated with the national People’s Climate Movement. The Colorado AFL-CIO and the Colorado People’s Alliance were co-chairs. The new coalition held a series of discussions between unions and environmental groups, sometimes guided by a professional facilitator, leading up to a Climate, Jobs, and Justice Summit. At a meeting of the Western States AFL-CIO, Colorado labor leaders learned about the Washington state Initiative 1631 and heard a presentation on Robert Pollin’s “A Green New Deal for Washington State” climate jobs report. Colorado unions thereupon commissioned Pollin to conduct a similar study for them.

Democrats won the legislature in the 2018 midterm elections and in 2019 moved to pass a bill to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by at least 90% from 2005 levels. That posed the question: What would be the law’s impact on workers and communities?

According to the Colorado Mining Association, Colorado is the 11th largest coal-producing state, with six active coal mines, employing a little over 1,200 mine workers. The National Mining Association estimates that nearly 18,000 people across Colorado are employed directly by the state’s mining industry. The proposed climate protection law would clearly have a significant impact on coal industry workers and communities.

Drawing on the experience of Washington Initiative 1631, unions and allies developed and passed the Colorado Just Transition law, HB-1314. Responding to fears about the human impact of energy transition, it focused on the needs of coal communities and workers. It instituted an Office of Just Transition and a Just Transition Advisory Committee including unions, corporations, economic development specialists, representatives of affected counties and disproportionately impacted communities, political leaders, and government officers—with a mandate to solicit input for a draft plan for workers and communities.

The law provides a “wage differential benefit” for workers who lose their jobs in a coal mine, coal-fueled electrical power generating plant, or the manufacturing and transportation supply chains of either. The wage differential benefit is defined as “supplemental income” covering all or part of the difference between an individual’s previous wages and their wages on their new job or their income during job retraining.

Dennis Dougherty said at first unions thought a “just transition” could mean demanding jobs in perpetuity at the same level of pay and benefits that workers are currently earning, but after doing research into the issue and assessing the political realities, they modified their demands.

We hired someone to research every ‘just transition’ that’s been done across the world. We said, okay, well what can we realistically do at the state level that we think is fair while also not coming out and demanding something that’s never going to happen?

The answer is embodied in the Colorado Just Transition law.

The law also provides grants to eligible entities in “coal transition communities” that seek to create a “more diversified, equitable, and vibrant economic future.” “Coal transition community” is defined as a municipality, county, or region that has been affected or will be affected by the loss of fifty or more jobs from a coal mine, coal-fueled electrical power generating plant, or the manufacturing and transportation supply chains of either.

At the end of 2020 the Office of Just Transition submitted a Just Transition Action Plan “to help workers continue to thrive by transitioning to good new jobs, and to help communities continue to thrive by expanding and attracting diverse businesses, creating jobs, and replacing lost revenues.” The plan required additional funding for implementation.

In March 2022 the Colorado General Assembly passed House Bill 22-1394 to provide an additional $15 million for the Office of Just Transition for coal workers impacted by the shift to clean energy. $10 million will go to the Coal Transition Worker Assistance Program; it will provide coal workers and their families funding to cover apprenticeship and retraining programs, childcare services, housing assistance, and other expenses. $5 million will support economic development in coal-dependent communities.

The workforce and community grant programs in the original 2019 Colorado Just Transition law were unanimously opposed by Republican legislators, who attacked them as “Orwellian,” “egregious,” and “offensive.” The new bill to help fund these programs passed 51-12 with bipartisan support. Republican Rep. Perry Will, who represents several coal-dependent communities in northwest Colorado, voted against the 2019 legislation that established the office, but praised HB-1394 on the floor of the Colorado House. “This is a much-needed bill. I appreciate the $15 million. I know we need more than this, but we’re pecking away at it a bite at a time, and this is very important to the communities I represent.”

Democratic Rep. Dylan Roberts said, “Towns like Hayden, Oak Creek, and Craig will be able to use this just transition funding to invest in projects that diversify rural economies, incentivize new energy jobs, and provide workers with supportive career service. This is the large investment in rural Colorado that our transitioning communities deserve, and I am thrilled this bill is moving forward with strong bipartisan support.” House Majority Leader at the time Daneya Esgar said, “This won’t be the last time a bill of this nature is going to come before you. We are going to continue to need to help these communities, help these workers, as we transition out of coal.”[6]

Protecting Workers and Communities in the Illinois Green New Deal

In September 2022, after months of difficult negotiations, the Illinois legislature passed the Climate and Equitable Jobs Act, incorporating programs laid out by both a labor coalition and a climate justice coalition. The Act commits Illinois to zero-carbon electricity by 2045 and a net-zero carbon economy by 2050 while advancing equity, justice, and quality jobs. Journalist Liza Featherstone called the legislation a “Green New Deal” for Illinois.[7]

The bill’s drafters were well aware of the possible adverse impacts of the energy transition on fossil fuel workers. The CEJA will close all fossil fuel plants by 2045. In 2019 four communities in central and southern Illinois were devastated when coal plants were closed with little warning. The CEJA accordingly incorporated a bill called the Energy Community Reinvestment Act. According to a fact sheet prepared by the Prairie Rivers Network, which advocated for just transition provisions for workers and communities in the CEJA, the Act includes these elements:

- An Energy Transition Workforce Commission will study impacts of plant and mine closures and prepare an Energy Transition Workforce Report with comprehensive recommendations on how to address the impact of the energy transition.

- Energy Transition Community Grants (funded at $40 million per year) helps communities to address economic and social impacts of the energy transition based on diverse community input.

- The Coal to Solar and Energy Storage program establishes renewable energy credits for solar projects and grants for energy storage facilities at former fossil fuel generating sites.

- The Renewable Energy Development program requires the Illinois Power Agency to optimize financial incentives to clean energy projects located in Energy Transition Community Grant areas.

- The Clean Jobs Workforce Network Program and Clean Energy Contractor Incubator Program create 13 workforce hubs and 13 contractor incubators to provide clean jobs training and support for clean energy businesses around the state. Displaced energy workers have priority for placement.[8]

- Displaced Energy Worker Dependent Transition Scholarship provides one-year full-time scholarships to a state-supported college or university for the children of displaced workers who demonstrate need.

The CEJA also includes a “Displaced Energy Worker Bill of Rights” to support fossil fuel power plant, coal mine, and nuclear plant workers who lose their jobs due to reduced operations or closures. The Bill of Rights includes:

- Advance notice of closures

- Financial advice

- Continued health care and retirement packages

- Full tuition scholarships at Illinois state and community programs

- Tax credits to businesses that hire displaced energy workers

Under the Displaced Energy Worker Bill of Rights communities that lose a fossil fuel power plant or coal mine can be designated as Clean Energy Empowerment Zones. They can be eligible for:

- Tax base replacement for up to five years for local governments, libraries, school boards, and other public services

- Economic development research assistance

- Incentives for clean energy companies to locate and invest

These programs are paid for by an Energy Community Reinvestment Fund, which collects money through a small fee on fossil-fuel pollution and a 6% Coal Severance Fee on coal extraction. The fund provides significant funding for the Climate and Equitable Jobs Act community and worker transition programs; for example, $100 million annually can be allocated to tax base replacement. [9]

Illinois programs for worker and community transition are already having an effect. Late in 2019 the Vistra Coal Plant closed in Havana, IL, and stopped paying taxes. The Havana Park District lost a third of its funding, cut staff, and shut down its Nature Center. In April 2022 the Havana Nature Center received the funding necessary to reopen its doors.[10]

California: “Looking at the Future”

California wildfires, global warming | Photo credit: Michael Penhallow, Canva Images

The Global Warming Solutions Act (AB32) of 2006 started California on a course of reducing its fossil fuel dependence and seeking a transition to a low-carbon future. AB32 was the first program in the country that created long term commitments to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. As of 2022, the state had shut down all but one coal-fired power plant. In 2018 state agencies approved a plan to close the Diablo Canyon Nuclear Energy facility, although policymakers reversed course in 2022, citing a lack of new power resources that will be ready before 2024. Hence in recent years the focus of fossil fuel phase-out has been on the state’s petroleum industry – oil and gas.

California’s nearly 160-year history of oil drilling is reflected in iconic images from the 1920s showing a forest of tall oil rig towers from the edge of the Pacific Coast in Huntington Beach. Later, city-size refinery campuses in Southern California and the Bay Area, and oil fields of the Central Valley, dominated local landscapes. Onshore and offshore drilling have had massive social and environmental impacts.

Environmental justice communities mobilized for more than a decade to end drilling in neighborhoods, finally passing bans on drilling in the city and county of Los Angeles in 2022.[11] Oil drilling isn’t the only source of fossil fuel pollution in the state. In 2015 a four-month long leak from Aliso Canyon’s underground storage facility caused then Governor Jerry Brown to declare a state of emergency in 2015.

Roughly 112,000 people are employed in California’s fossil fuel-based industries. 45% of them are people of color (below the state average of 63%) and 22% are women. While that number accounts for about 1% of California’s GDP and less than 1% of its workforce, pockets of the state are dependent on oil industry revenues. Kern county produces about 70% of the state’s oil; most of the rest of the state’s oil is produced around Los Angeles. In Kern County 15-20% of property taxes, which fund local schools, public health, roads, and infrastructure, come from oil and gas producers. California’s 15 refineries are clustered in Los Angeles and Contra Costa Counties. In those counties more than 60% of point source emissions come from these refineries.

From the turn of the 21st century California has been adopting policies to fight climate change by reducing greenhouse gas emissions. Today California is committed to cut GHG emissions by 50% by 2030 and to reach net zero emissions by 2045.

As California established fossil fuel reduction targets and adopted policies to implement them, the question of what would happen to fossil fuel workers and their communities came to the fore. Back when Jerry Brown was still governor, California’s Steelworkers union began working on a transition plan for their oil and gas workers. In 2019 labor climate activists organized official climate caucuses in the Alameda, Contra Costa, and San Francisco AFL-CIO labor councils. The Alameda Labor Council and the Labor Network for Sustainability co-hosted a Labor Convergence on Climate for 150 Bay Area labor leaders, members, and organizers at the hall of IBEW local 595, which discussed in depth how to protect California workers in the transition to a climate-safe economy.

Over the next year a group of unions continued to discuss how to protect workers and communities in the energy transition. They felt the need to move beyond vague rhetoric to concrete plans to protect workers whose jobs might be threatened. Hearing about studies done in other states by University of Massachusetts economist Robert Pollin, they commissioned Dr. Pollin to prepare a report on how to achieve California’s climate goals in a way that also protected workers.[12]

Pollin’s report was titled “A Program For Economic Recovery And Clean Energy Transition In California.”[13] The plan, promoted as the California Climate Jobs Plan, would reach California’s target of reducing carbon emissions by 50% by 2030 — and create more than a million jobs. The state would create 418,000 clean energy jobs per year through a program to cut climate pollution in half over the next decade. It would create 626,000 additional jobs per year through investments in related areas such as water infrastructure, leaky gas pipelines, public parks, and roadways. Unique to the roll-out of this plan is the fact that oil workers are getting behind a transition to renewable energy.[14]

The plan included specific provisions for workers and communities that might lose jobs in the transition. It proposed “wage insurance” for fossil fuel workers to guarantee new jobs with three years’ worth of total pay at the same level as their old fossil fuel employment. It also provided coverage for pension obligations, retraining, and relocation. The cost is estimated at $470 million per year, or 0.02% of California’s expected GDP. Twenty California unions, including steelworkers, municipal workers, teachers, and three unions representing thousands of oil workers, endorsed the plan.

Elements of the “California Climate Jobs Plan” are now moving forward on several fronts. The state budget also includes $40 million in a fund for displaced oil and gas workers, a pilot program possibly targeted to workers who will be affected by the shutdown of oil wells or refineries. In 2020 Los Angeles County established a Just Transition Task Force initially focused on capping and cleaning up LA’s more than 2,000 idle and abandoned oil wells. The task force mandate includes developing labor standards for well capping. Then-LA Supervisor Mark Ridley-Thomas, who brought the motion for Just Transition for LA, said, “As we transition, we must ensure it is a just transition.” We have an opportunity here “to wed our environmental goals with a meaningful workforce agenda.”[15]

From Economic Individualism to Social Provision

So-called “economic individualism” has been a continuing feature of American life. Even when adversity is obviously a product of social causes like depressions and technological changes, US economic policy has generally left working people on their own to cope with the impact on their lives. The main exceptions originated in the Great Depression, where mass misery and its threat to social stability led to the unemployment insurance and social security systems. These have never provided more than a fraction of an adequate livelihood, however. Nor has the US ever implemented industrial location policies designed to counter the devastating impact of economic change on localities, states, and regions.[16] The few attempts to compensate individuals for the devastating impacts of economic policies on their lives, such as the Trade Adjustment Assistance offered to workers affected by policies promoting globalization, have merely provided a pittance to a small proportion of affected workers.

As a result, protection for workers and communities affected by climate policies has been slow to develop. Such protection has few precedents, and it meets virulent opposition from those who advocate economic individualism and oppose social provision of any kind. Some proponents of climate protection policies have maintained that they will produce so many new jobs that it is unnecessary to have specific policies to protect those who may lose theirs, ignoring the barriers that may prevent former fossil fuel workers from gaining access to those new jobs. As federal policy has haltingly moved toward climate protection, it has done little to protect workers and communities from the consequences.

Just as states have stepped into the breach to develop their own greenhouse gas reduction laws and policies, so have they begun to address the unintended negative side effects that may come with those measures – to provide what is sometimes referred to as a “just transition.” While they have few precedents to draw on, the examples we have examined from Washington, Colorado, Illinois, and California show that a new approach is possible, and that it is in fact being invented.

These inventions have followed a common pattern. They have been initiated when public opinion supporting state climate protection policies has become irresistible. At that point current and aspiring state political leaders have come to support targets for greenhouse gas reduction and means to reach those targets. But that is soon perceived as threatening workers and communities dependent on the fossil fuel economy. That concern may initially generate opposition to climate protection policies – and particular communities and groups of workers may be held up as “poster children” for the negative effects of climate policies. The result is often an augmentation of the purposed opposition of “environment vs. jobs,” and an aggravation of conflict between environmentalists and organized labor (often gleefully promoted by fossil fuel interests).

But three shifts in mindset sometimes begin to create an alternative to that opposition. First, trade unionists begin to recognize that change in energy systems is coming whether they like it or not, and that their members will be vulnerable to that change unless policies are adopted to protect them. Second, climate protection advocates begin to see that there will be massive opposition to the policies they advocate unless they recognize and act on their responsibility to also protect those who those policies may adversely affect. Third, the underlying idea of the Green New Deal — that climate protection offers an opportunity to address inequality and injustice – opens a vista for social change that goes beyond the pursuit of narrow interest politics. This “new thinking” may initially be based on particular interests, but it may also be encouraged by the development of a broader awareness in unions of the necessity for climate protection, among environmentalists of the necessity for community wellbeing, and among justice advocates of the potential of new coalitions to overcome long-established injustice.

The result has been the development of coalitions among groups that had previously been at odds, lobbing virtual projectiles at each other from separate silos. These coalitions often start with simple exploratory efforts, such as workshops, forums, and convergences. The discovery of common ground may lead to an informal or formal coalition, often defined at first more by a sense of common interests than by agreement on specific policies. In many cases the next step has been to commission an expert report laying out how to protect workers and communities while reducing greenhouse gas emissions.[17] That has laid the basis for negotiations – often lasting a year or more – to develop agreement around a specific policy agenda. Then, generally with the help of sympathetic political leaders, specific language is developed that can be included in legislation. That is followed by definition of a strategy to implement the legislation and a campaign of public education and a mobilization of public support. Whether they are successful or not, these efforts often redefine the public debate and the frameworks within which public policy is determined; even campaigns that lose can transform the landscape for future possibilities both locally and beyond. If policies are successfully passed into law, the coalitions must turn to seeing that they are implemented in a way that fulfills their original objectives.

The policies developed have often combined the needs and objectives of the different coalition members. They include or are included in the most advanced state policies for reducing greenhouse gas emissions. They provide direct help for laid off fossil fuel workers, such as career guidance, education and training, help finding new jobs, hiring preferences, supplemental payments when new jobs pay less than previous ones, health insurance, pension protection, and retirement benefits. They provide help for communities affected by mine and power plant shutdowns, such as payments to help compensate for lost taxes, support for economic development planning, incentives for employers to locate in affected communities, and investment in economic and infrastructure development. They often require that a substantial proportion of funds be allocated to low-income and otherwise deprived communities.

These policies have the potential to open the way to longer-term changes in public policy. For example, wage guarantees and supplements could develop into a more robust social provision for the needs of those who, through no fault of their own, have their lives devastated by economic change. Harm-free transition from fossil fuels to clean energy requires extensive planning; community protection policies are making a start in that direction. It also requires public investment since private investment has proven unable to undo the damage of private disinvestment. Programs like the Illinois Energy Community Reinvestment Fund begin to accept public responsibility for developing jobs and taxable enterprises in the communities that need them most. Requirements for participation of diverse segments of local communities in planning and implementing programs could serve as a jumping-off point for broader forms of democratization of economic development.

In an economy that is national and indeed global there are undoubtedly limits on what state policies can accomplish. The Biden administration has made some small initial steps toward addressing the downsides of energy system change, for example its Interagency Working Group on Coal and Power Plant Communities and Power Plant Revitalization which is providing assistance to communities affected by mine and power plant closings.[18] The state legislation and programs described above provide an indication of what is needed at a federal level – and at a much larger scale.

Given our national political deadlock, such a program is not on the immediate federal agenda. But it is an essential part of the long-term agenda often referred to as the Green New Deal. The state and local programs for protecting workers and communities, described in this and the preceding Commentaries, form an essential part of what we have called the Green New Deal from Below.[19]

When once-divided groups reach out to each other, explore common needs and interests, and start cooperating for common objectives they thereby create new forms of social action. That is the process that I have elsewhere called the emergence of “common preservation.”[20]

[1] C.J. Polychroniou, “Oil Companies Spent Millions To Defeat Green New Deal In Washington State,” Rozenberg Quarterly, https://rozenbergquarterly.com/oil-companies-spent-millions-to-defeat-green-new-deal-in-washington-state/

[2] David Roberts, “Washington I-1631 results: price on carbon emissions fails to pass,” Vox, November 6, 2018. https://www.vox.com/energy-and-environment/2018/9/28/17899804/washington-1631-results-carbon-fee-green-new-deal For more on the climate justice work of the coalition see Sasha Abramsky, “This Washington State Ballot Measure Fights for Both Jobs and Climate Justice,” The Nation, July 20, 2018. https://www.thenation.com/article/archive/green-new-deal-evergreen-state/ For Front and Centered see: https://frontandcentered.org

[3] Robert Pollin, Heidi Garrett-Peltier, and Jeannette Wicks-Lim, “A Green New Deal for Washington State: Climate Stabilization, Good Jobs, and Just Transition,” PERI, December 2017. https://peri.umass.edu/component/k2/item/1033-a-green-new-deal-for-washington-state

[4] “Initiative Measure No. 1631,” Washington Secretary of State, March 13, 2018. Initiative Measure No. 1631

[5] Rachel M. Cohen, “The Just Transition for Coal Workers Can Start Now. Colorado Is Showing How.” In These Times, July 24, 2019. https://inthesetimes.com/working/entry/21975/colorado-just-transition-labor-coal-mine-workers-peoples-climate-movement

[6] Chase Woodruff, “As coal burning goes away in Colorado, money for coal workers goes up,” Colorado Newsline, April 30, 2022. https://coloradonewsline.com/2022/04/30/just-transition-colorado-coal-workers-rural-communities-advanced/

[7] Liza Featherstone, “Illinois Just Won a Big Green Jobs Victory,” Jacobin, September 21, 2021.

https://jacobin.com/2021/09/illinois-green-new-deal-jobs-labor-nuclear For an overview of the legislation see Jeremy Brecher, “The Green New Deal in the States – Part 1,” Commentaries on Solidarity and Survival, forthcoming.

[8] “Energy Community Reinvestment Act Fact – CEJA” Prairie Rivers Network, https://docs.google.com/document/d/1q23G-pfUqrNInX7tG19Nr9ooyHcOeFxOVQ9NGYNV9iE/edit

[9] “The Clean Energy Jobs Act,” Illinois Clean Jobs Coalition. http://ilcleanjobs.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/JustTransition.pdf

[10] “Reinvesting in Illinois’ Energy Communities.” Prairie Rivers Network, May 23, 2022. https://prairierivers.org/front-page/2022/05/reinvesting-in-illinois-energy-communities/

[11] Kacey Bonner, “ STAND-L.A. Demands Change While Celebrating Major Community Victory for Environmental Justice in LA as City Moves to Phase Out Drilling,” STAND-LA, December 2, 2022. Press release from STAND.LA on LA City’s ordinance to prohibit new oil and gas extraction and phase out existing drilling citywide – http://www.stand.la/campaign-updates.html.

[12] The Labor Network for Sustainability and San Francisco Jobs with Justice helped coordinate the study.

[13] Robert Pollin, Jeannette Wicks-Lim, Shouvik Chakraborty, Caitlin Kline, and Gregor Semieniuk, “A Program For Economic Recovery And Clean Energy Transition In California,” Political Economy Research Institute (PERI), June 2021. https://peri.umass.edu/publication/item/1466-a-program-for-economic-recovery-and-clean-energy-transition-in-california See also “Twenty Unions Stand By a California Climate Jobs Plan,” Making a Living on a Living Planet, July/August 2021. https://labor4sustainability.ourpowerbase.net/civicrm/mailing/view?reset=1&id=675 For a list of unions endorsing the California Climate Jobs Plan see https://www.californiaclimatejobsplan.com

[14] Sammy Roth, “Why a California oil workers union is getting behind clean energy,” LA Times Boiling Point, June 10, 2021.https://www.latimes.com/environment/newsletter/2021-06-10/why-a-california-oil-workers-union-is-getting-behind-clean-energy-boiling-point

[15] Monica Embrey, “Los Angeles County Forms Just-Transition Taskforce to Clean Up Old Oil Wells,” Sierra Club, September 29, 2020.

[16] J. Mijin Cha, Vivian Price, Dimitris Stevis, and Todd E. Vachon, “Just Transition Listening Project,” Labor Network for Sustainability. https://www.labor4sustainability.org/jtlp-2021/

[17] Three of the four cases in this Commentary included reports by economist Dr. Robert Pollin and the Political Economy Research Institute (PERI) at the University of Massachusetts Amherst.

[18] For a review of the Interagency Working Group’s activities so far, see “Interagency Working Group (IWG) on Coal and Power Plant Communities and Economic Revitalization,” Congressional Research Service, October 24, 2022. https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/IF/IF12238

[19] See Jeremy Brecher, “The Green New Deal – From Below,” Labor Network for Sustainability, October 22, 2021. https://www.labor4sustainability.org/strike/the-green-new-deal-from-below/ and subsequent commentaries in this series.

[20] Jeremy Brecher, Common Preservation in a Time of Mutual Destruction (Oakland, CA: PM Press, 2021). https://pmpress.org/index.php?l=product_detail&p=1095