by Leo Blain

What were you doing when you were 15? Homework, sports, parties, dances: these are standard fare for 15 year-olds.

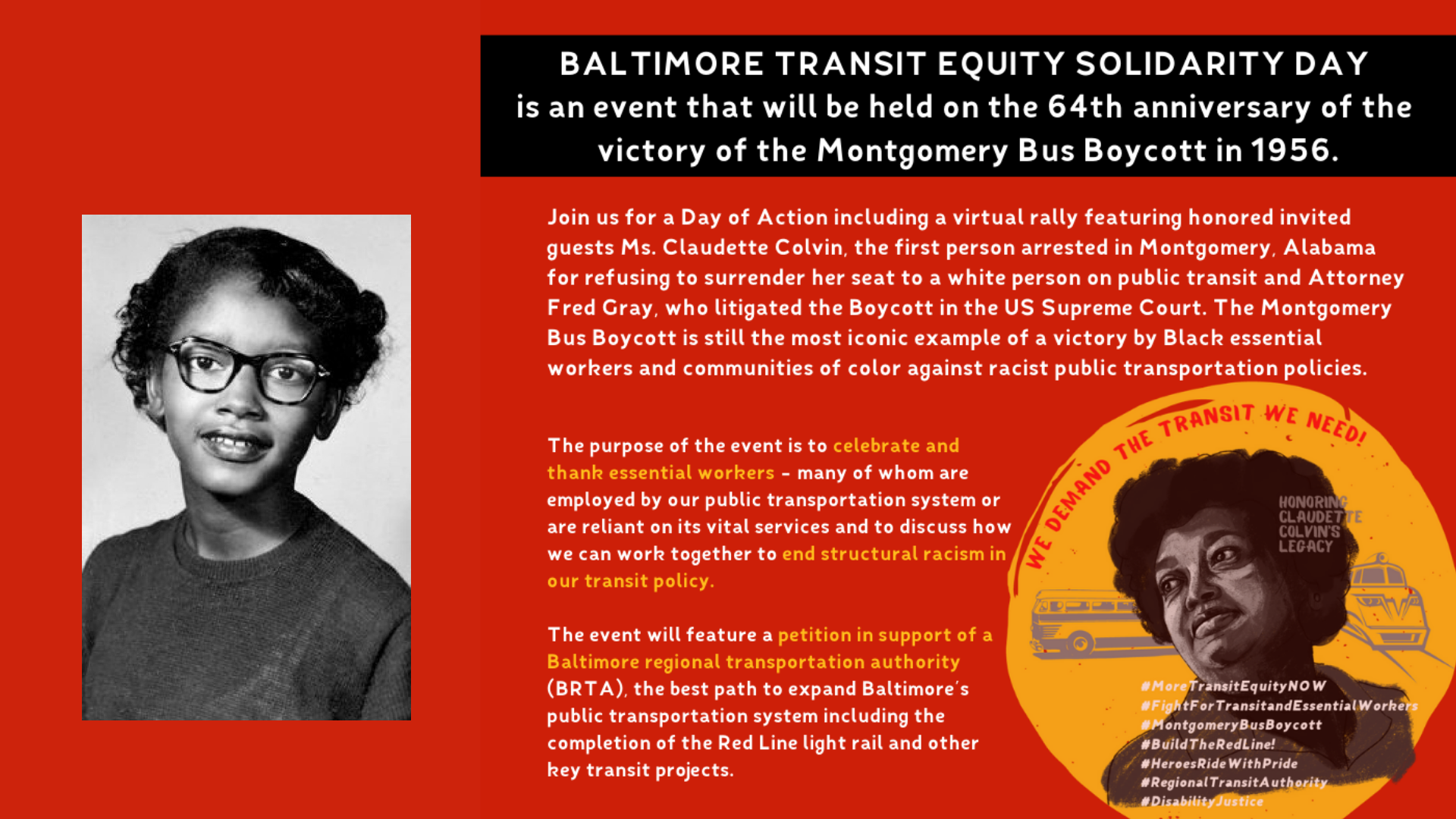

Claudette Colvin was no standard 15-year old, though. When she was 15, she sat down on a Montgomery, Alabama bus and refused to give up her seat to a white person. She was arrested and wrongfully charged with assault and battery. Despite being just 15 at the time of her arrest, Colvin was booked into a cell in Montgomery’s adult jail. When Colvin’s pastor, Reverend H.H. Johnson bailed her out the evening of her arrest, he told her that she had “just brought the revolution to Montgomery.”

And, she did it on March 2, 1955: Nine months before Rosa Parks’ similar and much more famous action.

Colvin brought a lawsuit along with three other women that went all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court and led to the legal desegregation of the Montgomery bus system. When the Montgomery bus system was desegregated Colvin wasn’t invited on the first desegregated bus. Neither was Parks. In fact, none of the women who were among the first to be arrested in protest of the segregated bus system were invited. Five men took the first ride: Martin Luther King Jr., E. D. Nixon, Ralph Abernathy, and Glenn Smiley, and Colvin’s lawyer, Fred Gray. [2]

Spurred by what she had learned in Black history classes at school, Colvin was the first person to be arrested for refusal to surrender in Montgomery. She was the first person in Montgomery to make a legal claim that transit segregation violated her constitutional rights. The contemporary civil rights movement starts with Claudette Colvin’s act of near-unconscionable bravery, yet she has been largely erased from the history books.

After Colvin’s arrest, she was ostracized by many community members and struggled to find work after high school. She got pregnant soon after her arrest, and due to her pregnancy and the preference of civil rights leaders for Rosa Parks as the face of the boycott, Colvin was largely cast aside by the very movement she had sparked. Ultimately, her perception in Montgomery became untenable and she moved to the Bronx where she worked in relative obscurity as a nurse.

In recent years, though, Ms. Colvin has found a champion in movement leaders such as Samuel Jordan, founder of the Baltimore Transit Equity Coalition. For Jordan, telling Colvin’s story is both long overdue and a critical piece of his work towards transit equity in Baltimore and nationwide. Baltimore has a pattern of public transit policy that is harmful to marginalized residents and has been used to manipulate Black youth. If Claudette Colvin’s story of taking a bold stand against transit inequity can get the attention it deserves, maybe the young people who are victims of transit inequity today can have their voices heard too.

2015 Baltimore Protests

A prime example of manipulative public transit policy in action came in Baltimore on April 27, 2015, eight days after Freddie Gray was brutalized and killed by Baltimore police. At the behest of the Baltimore police, the Maryland Transit Authority (MTA) shut down public transit at Mondawmin Mall, a major transit hub across the street from historic Frederick Douglass High School.

Each day, 5,000 high school students stream through the mall to public busses that take them to and from school. But on April 27, 2015, MTA halted service right as school let out. When students arrived at the mall to find themselves stranded by MTA, police were already waiting for them. The accounts of what happened next–and whether police or students were responsible–differ greatly depending on who’s telling the story.

This Time Magazine account of the event completely disregards MTA’s shutting down public transit at the request of police right as school was letting out. Instead, the article claims the timeline of events started at 3:30 with “kids… throwing bottles and bricks at police officers.” Other media and the police account of the event also ignore or obscure that the students were unknowingly trapped in Mondawmin Mall by the police and MTA. In one of the few accounts of the event that doesn’t blame the students for the carnage, ProPublica reporter Alec MacGillis lamented the blundering incompetence of Baltimore officials:

It was almost as if authorities were trying to engineer the confrontation that ensued between the growing mass of stranded youths and the outnumbered cops. Rocks and debris were hurled in both directions: Ramallah in Baltimore. So ill-conceived was the decision that, even after months of pressing by local reporters, no one claimed credit for having issued it — not the mayor’s office, not the transit system, not the schools, not the cops. The closure became an act of nature, as unavoidable as a power failure in a storm: transit was shut down. (Source: “The Third Rail,” Alec MacGillis)

To date, neither the Baltimore Police Department or the City of Baltimore have apologized or even acknowledged the reality of what happened on April 27, 2015. Public transit is “an instrument of the control of people of color,” Jordan says. “Always has been.”

The injustices of April 27, 2015 and their erasure from the public record have led Jordan to wonder: How many Claudette Colvins were among the thousands of young people corralled at Mondawmin Mall? Jordan describes how “the stories we’ve heard from the young people [who were] there are not full of braggadocio…it’s, ‘Why are we being pushed around by the police?’ And the police have given no explanation except, ‘Move when we say move.’”

Those experiences–cruelty beyond reason directed at students–are what worry Jordan most. After braving police brutality to stand for what she believed was right Claudette Colvin was largely cast aside and denied the life she was due. Jordan believes that if the stories of the Baltimore students aren’t told, we’ll lose more brave young people to the same unjust circumstances that have framed Claudette Colvin’s life: brutality followed by erasure.

What does justice look like?

According to Jordan, justice means breaking the decades-long pattern of the subjugation and erasure of young Black voices at the hands of transit inequity and racist public transit policy. A good place to start, he thinks, is with the recognition of Colvin’s struggle as well as recognition of the abuse suffered by the Baltimore students. Jordan is eager to build a campaign for Colvin to be awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom, just like Rosa Parks. And, he wants accountability from Baltimore and the MTA. “The city owes the young people an apology,” he says. “There needs to be an apology. Young people were traumatized.” This time around, the stories of those young people can’t disappear.

Leo is a Content Producer at the Labor Network for Sustainability and a full-time student at Guilford College, North Carolina.